Over the last number of years, the topic of acid-base balance has become a very popular health topic. The bulk of the focus has been on dietary means to support the body’s internal acid-base environment, so as to promote a more alkaline (base) milieu. Both diet and supplement measures have been theorized and/or explored for general health and in the management of specific concerns, such as osteoporosis. Research is beginning to elucidate this connection, however, as recent evidence seems to dispel the notion that an acid-forming diet negatively affects bone health.[1] More recently, evidence is emerging which shines the “pH balance light” on skin health. Interestingly, we are beginning to more thoroughly understand and appreciate the importance of establishing and maintaining a more acidic environment for the surface of the skin. This article will explore the dynamic role an acidic skin surface plays in the context of both maintaining healthy skin and managing common skin concerns. Methods of encouraging this acid mantle, as it’s called, will also be reviewed.

The pH Picture

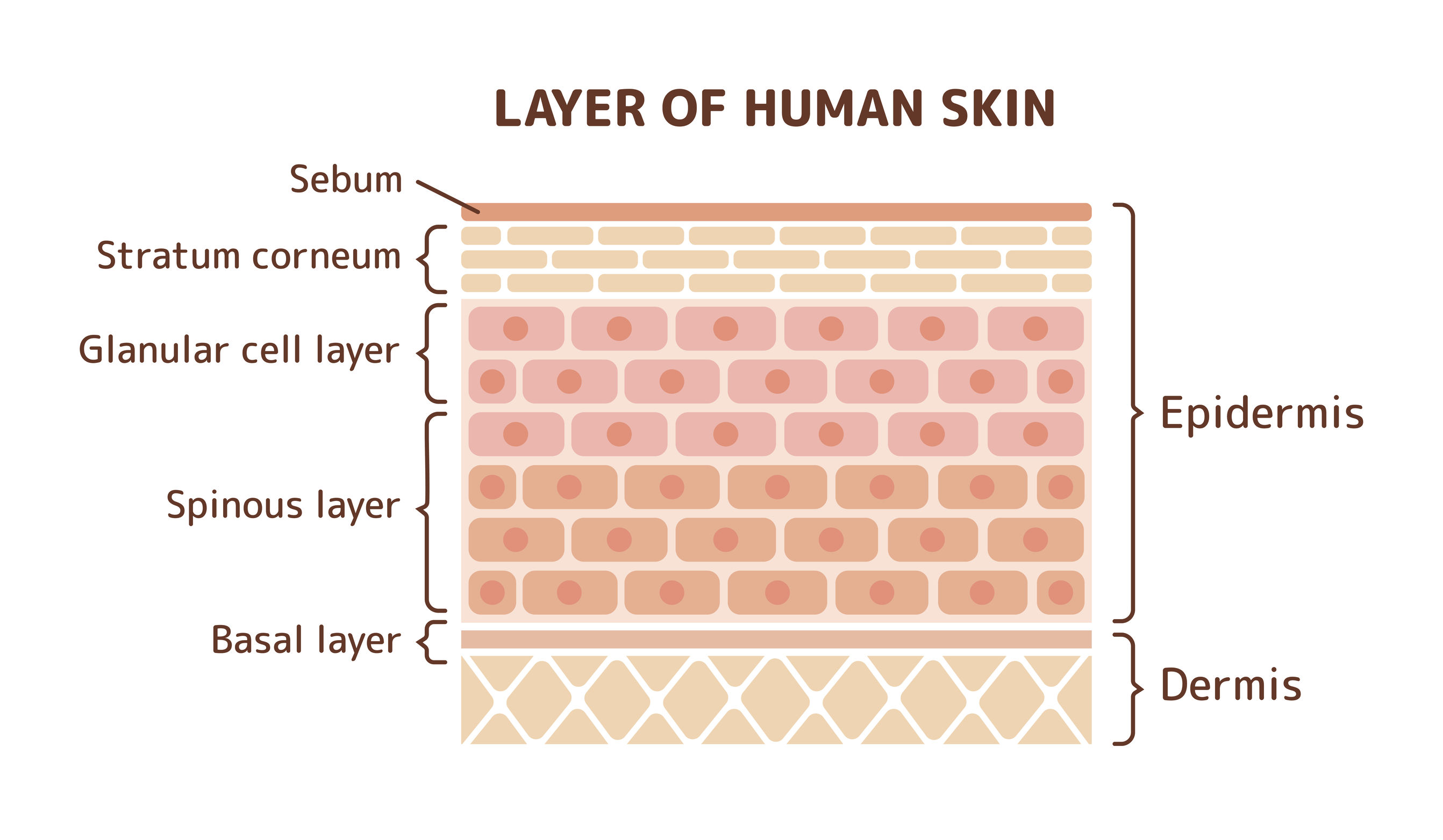

pH refers to “potential hydrogen,” and within its scale of 0–14, it provides an insight as to acidic (under 7) or basic/alkaline (above 7) a substance, or area of the body, can be. A pH of 0 would signify maximum acidity while, by contrast, that of 14 signifies maximum alkalinity. Generally speaking, maintaining a slight alkaline environment supports optimal body processes and functioning. While the human body’s internal environment, and in particular blood, maintains a slightly alkaline pH of around 7.4, the skin seems to play by a different set of rules. Optimal skin pH is actually acidic, falling in the range of 4–6 on the pH scale. What’s even more interesting is that the strongest degree of acidity is found at the uppermost level of the skin’s outermost layer.[2] We’ll delve into that last point a little further. As you may remember from my previous articles, the skin’s upper layer, the epidermis, is itself segregated into various layers. The stratum corneum sits at the very top and is composed nondividing cells known as corneocytes. These corneocytes are layered together into multiple sheets. It’s at this level of the stratum corneum that the skin is kept acidic. As one moves from the outermost sheet of corneocytes, progressively down each sheet toward the lowest layer of corneocytes, the pH increases (i.e. becomes more neutral/alkaline), ultimately reaching a neutral pH of around 7 as we reach the next layer below the stratum corneum, that of the stratum granulosum.[2]

The Acid Mantle

The skin has developed a wide variety of methods to help maintain the acidic nature of the stratum corneum layer, sometimes referred to as the “acid mantle.” Any interference with these processes, some of which we will review below, can result in the disruption of the acid mantle and predispose the skin to various cosmetic and dermatological concerns. Some of these processes include:[2][3]:

- The release of lactic acid from sweat gland secretion;

- The generation of free fatty acids from the breakdown of lipids naturally found in the skin;

- Enzyme-based generation of free fatty acids from bacteria and oil-producing glands naturally on and within the skin;

- The production of urocanic acid from the metabolism of the amino acid histidine; and

- The generation of amino acids from the breakdown of structural components naturally found in the stratum corneum, such as filaggrin.

Skin pH and the Skin Barrier

An acidic stratum corneum is essential for the functioning of the skin barrier system. Shifts in the skin pH have been found to predispose to various inflammatory and infectious skin concerns, including acne and eczema/atopic dermatitis. My previous articles have also reviewed the importance of maintaining the skin barrier. This includes both the corneocytes we described above, embedded within a lipid matrix consisting of ceramides, cholesterol, and fatty acids. The barrier plays an essential role in maintaining optimal skin hydration and, true to its name, acting as a barrier against the entry of irritating and inflammatory-triggering substances into the deeper skin layers. Many skin concerns are recognized as having skin-barrier disruption as part of their pathological processes.[4] Connections between the acid mantle and the skin barrier include ways by which the lipid matrix formation is acid-dependent. Examples of this include:[2]

- The enzymes in the skin which help synthesize ceramides require an acidic environment; and

- Formation and processing of the lamellar body vesicles in keratinocytes (the cells which eventually transition into corneocytes) which contain ceramides and lipids necessary for lipid matrix formation, also require an acidic pH.

Skin pH and Acne

In addition to the impact on the skin barrier, skin pH changes can further play a role in acne development:[2]

- pH and Bacterial Flora: Increased (i.e. less acidic) skin pH leads to increases in the population and activity of Propionibacterium acnes and other microbes, possibly owing to the reduced action of antimicrobial peptides. Inflammatory response in relation to the presence of P. acnes is a key factor in acne lesion development.

- pH and Sebum: Acne-associated sebum secretion carries a lower free fatty acid content, potentially lowering its contribution to the acid mantle formation.

- pH and Hormones: Androgens such as testosterone and dihydrotestosterone, which can be elevated in cases of acne, can inhibit lamellar body vesicle formation and secretion into the extracellular space, and have been found to negatively impact barrier repair/recovery. Such an effect on lamellar bodies can also interfere with its contribution to acid-mantle formation.

- Skin pH and Atopic Dermatitis (Eczema)

Eczema is a chronic inflammatory skin concern generally characterized by areas of red, scaly, dry, and itchy skin. Multiple lines of evidence show how, in those suffering from eczema, there exists a higher skin pH across multiple areas of skin. This includes even areas which are not actively showing skin symptoms.[3] Further connections include:[3]

- Up to 50% of those with atopic dermatitis exhibit a genetic mutation which leads to a decrease in filaggrin, a key structural protein in the stratum corneum, and as we saw above, a contributor to the acid mantle.

- Studies have found that, while elevated skin pH is consistent in the occurrence of eczema, the degree/extent of the increase can be dependent upon disease factors such as the severity and chronicity of symptoms; itch intensity; degree of skin involvement; genetic predisposition to filaggrin gene mutations; and skin dryness.

- Role in sensitive skin? Skin that is regularly at a higher pH can more easily be irritated by skin-care ingredients with a known irritative profile, such as sodium lauryl sulfate.[2]

What We Can Do to Maintain the Acid Mantle

There are a few methods by which we can encourage a lower skin pH: cleansing with the appropriate face and body wash products; utilizing cleansers/moisturizers designed with a low pH; and, potentially, nutritional interventions. We will explore each of these below. As always, prior to making adjustments to your skincare or health regimen, please first consult with your local health-care/skin-care provider to confirm if these approaches would be suitable in your case.

1. Cleanser Selection

In my previous article exploring cosmetic ingredients in managing acne, I had reviewed the differences between, and typical ingredients found in, various types of face/body washes. Traditional, or “true,” soaps contain a stronger degree of detergent activity which not only can remove the essential lipids found in the lipid matrix of the skin barrier but are also very alkaline and can thus increase skin pH. This will further interfere with skin-barrier maintenance and can act as an irritant for sensitive, acne-prone, and eczema-prone skin. By contrast, synthetic detergents (aka syndets) and oil-free cleansers are both designed to effectively clean skin, while leaving behind a moisturizing layer. They are also both typically more acidic, thus further supporting the maintenance of the acid mantle. The impact of syndets and oil-free cleansers on skin pH is both short-term (lasting for two hours immediately postwashing), and long-term (with use of two facial washings per day for at least one minute each). The change in skin pH is directly proportional to the pH of the cleanser. On a related side note, some individuals may have grown accustomed to simply using plain tap water, without any cleanser, to clean the face. However, this can be problematic, as plain tap water typically has a pH around 8 and can temporarily increase skin pH for up to six hours.[2]

2. Acidic Emollient Moisturizers

Recent research is now pointing to the role that moisturizers—and in particular those containing emollient-based moisturizing ingredients such as dimethicone, cyclomethicone, cetyl stearate, and soy sterols, among others—can play in further acidifying the stratum corneum after the cleansing process. In the case of eczema, for example, an ideal moisturizer would not only reduce dry skin, but also contain ceramides and be formulated at a low pH, ideally no higher than a pH of 5.[3][5][6] It may be wise, when exploring skin-care cleansers and moisturizers, to begin to inquire about the pH the product is formulated at.

3. Nutritional Interventions

Although much more study is needed in this area, small preliminary reports indicate that reduced (acidic) skin pH has been associated with regular fluid intake as well as dietary intake of vitamin A (think orange and dark greens, such as sweet potato, carrot, swiss chard, kale, spinach), calcium (in addition to dairy, think soy/tofu, and the greens like collard greens, mustard greens, spinach), monounsaturated fatty acids (think extra virgin olive oil), and histidine (owing to urocanic acid production described earlier; histidine-rich foods include all animal and seafood products; and from plant sources, legumes, nuts, seeds, vegetables such as cauliflower, corn; fruit such as banana, citrus fruit, and cantaloupe; and whole-grain wheat, oat, barley, rice, and buckwheat).[2][7]

As new evidence emerges regarding the role of skin pH, it is helping us better appreciate and understand how much of an avenue it offers in the management of various skin concerns. It also underlines just how much common everyday cleansing and moisturizing practices, and the products used for them, can play in supporting the acid mantle, and thus overall skin health.

Niacin is one form of vitamin B3. Niacinamide and inositol hexanicotinate are the other two forms of B3 that exist; these forms are generally used to treat different conditions within the body. B vitamins ultimately help the body utilize fats and proteins; they also help convert food into fuel which is then used to produce energy.

Niacin is one form of vitamin B3. Niacinamide and inositol hexanicotinate are the other two forms of B3 that exist; these forms are generally used to treat different conditions within the body. B vitamins ultimately help the body utilize fats and proteins; they also help convert food into fuel which is then used to produce energy. Noticing blood while brushing or flossing can be alarming and shouldn’t be ignored! The importance of oral health is a concept introduced to most Canadians at a very young age, and with good reason. The Ontario Dental Hygienist’s Association reports that the link between oral infections and other diseases in the body is becoming well-documented and accepted within the health-care community. Periodontal disease is one of the most common human diseases

Noticing blood while brushing or flossing can be alarming and shouldn’t be ignored! The importance of oral health is a concept introduced to most Canadians at a very young age, and with good reason. The Ontario Dental Hygienist’s Association reports that the link between oral infections and other diseases in the body is becoming well-documented and accepted within the health-care community. Periodontal disease is one of the most common human diseases Periodontitis is the result of gingivitis progressing to a more serious stage. It is characterized by swollen, reddish, and bleeding gums, as well as bad breath. Severe periodontitis affects 10–15% of adults, while moderate periodontitis affects 40–60% of adults. Despite its high prevalence, it is largely unrepresented as a chronic inflammatory disease.

Periodontitis is the result of gingivitis progressing to a more serious stage. It is characterized by swollen, reddish, and bleeding gums, as well as bad breath. Severe periodontitis affects 10–15% of adults, while moderate periodontitis affects 40–60% of adults. Despite its high prevalence, it is largely unrepresented as a chronic inflammatory disease. And so it begins. You find few strands of hair on your pillow and more than the usual amount on your hair brush. As you are cleaning your house, you begin to notice hair on the floor, in the shower, on your clothes, and then it dawns on you that you are not only leaving behind a trail of hair in every area of the house, but a hairless patch possibly somewhere on your scalp.

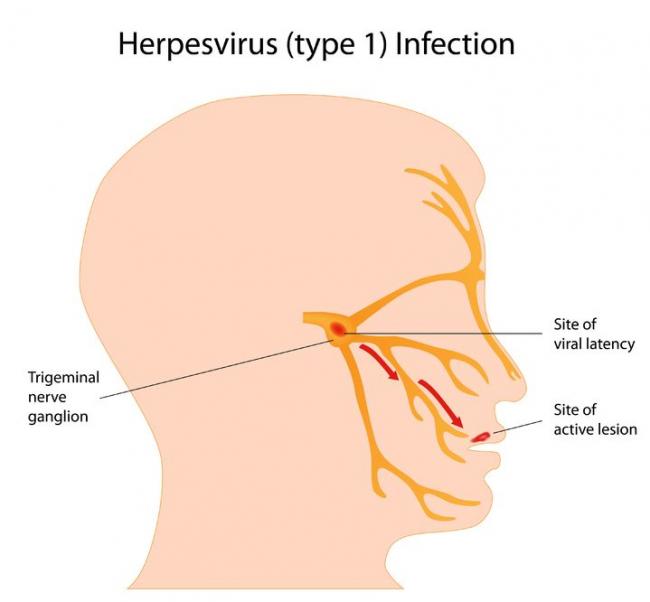

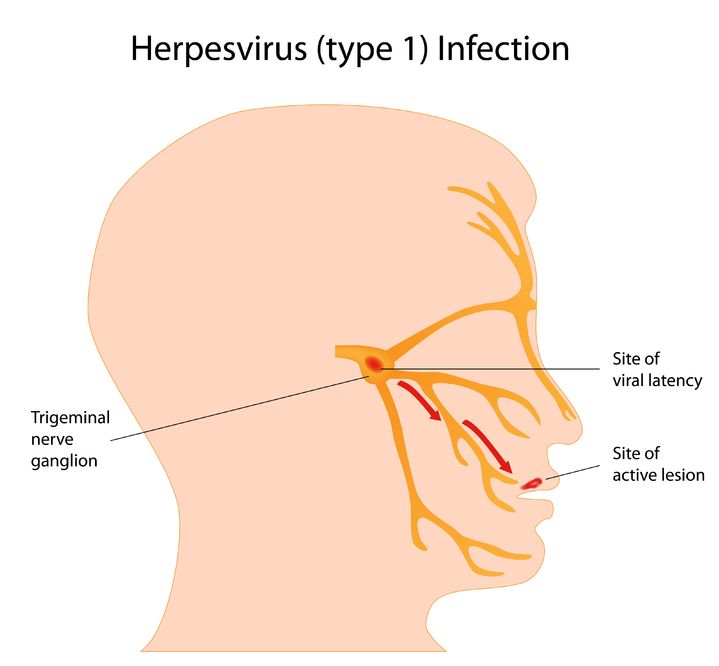

And so it begins. You find few strands of hair on your pillow and more than the usual amount on your hair brush. As you are cleaning your house, you begin to notice hair on the floor, in the shower, on your clothes, and then it dawns on you that you are not only leaving behind a trail of hair in every area of the house, but a hairless patch possibly somewhere on your scalp. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a viral infection of the skin and mucous membranes. Lesions can occur in many different areas, especially in or around the mouth, lips, genitals, and eyes. There are two types of HSV that exist: HSV-1 and HSV-2. HSV-1 is responsible for the development of your typical “cold sore”; it therefore has a predisposition for the mouth and lips,

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a viral infection of the skin and mucous membranes. Lesions can occur in many different areas, especially in or around the mouth, lips, genitals, and eyes. There are two types of HSV that exist: HSV-1 and HSV-2. HSV-1 is responsible for the development of your typical “cold sore”; it therefore has a predisposition for the mouth and lips, Who we are and how we feel is often expressed through our hair. Regardless of if hair is curly, straight, twisted, corn-rowed or locked; it is a universal sign of beauty, sensuality, fertility and attractiveness. Moreover, hair helps us to communicate our state of health. It also serves the function of protecting our heads and skin, adding not only a layer of insulation, but also more dimension to our personalities.

Who we are and how we feel is often expressed through our hair. Regardless of if hair is curly, straight, twisted, corn-rowed or locked; it is a universal sign of beauty, sensuality, fertility and attractiveness. Moreover, hair helps us to communicate our state of health. It also serves the function of protecting our heads and skin, adding not only a layer of insulation, but also more dimension to our personalities.