Related Articles

- 15 Jun 21

Medium-chain triglycerides, or MCTs, have been popularized in the context of Bulletproof™ coffee or the ketogenic diet. MCTs and the keto diet have been investigated in the management of obesity, insulin resistance, , epilepsy, neurodegenerative conditions, and others.

- 12 Feb 20

Endometriosis is one of the most common chronic gynecological conditions in women of reproductive age. Not only is it associated with severe, debilitating pain, but it can also have significant implications for a woman’s fertility.[1]

- 29 Jan 21Adrenal fatigue affects individuals who suffer from a long stretch of physical, mental, environmental, or emotional stress. A “long stretch” can be defined as greater than three months. Adrenal fatigue can affect anyone, but individuals who are more likely to suffer from adrenal fatigue include single parents, individuals who are drug-dependent, those who have faced a life crisis or trauma, or those who have a stressful job circumstance.

- 05 May 20

Diabetes is a common condition of the modern world, with rates of prevalence on the rise. The International Diabetes Federation estimates that in 2019, 463 million adults currently had diabetes, with a projection for this to increase to 700 million people in the next 25 years. For Canadian adults, diabetes is the number one cause of blindness, end-stage renal disease, and amputations unrelated to trauma.

- 29 Apr 22

Probiotics have extensive potential for therapeutic use, and we continue to discover their specific actions. The previous article looked at classification and the role of probiotics with regards to immune function and digestion, including autoimmunity, atopic skin reactions, and respiratory conditions.

- 09 Jan 20

Fasting has been around for generations as part of cultural spiritual practices. Today, it is used for proper weight maintenance, healing from disease, and prevention. Humans are metabolically flexible: We are able to change the source of energy that we use to power our cells depending on the available resources. Ultimately, it is the production of ketones that generates the healing ability of a fast, disease prevention, and increased longevity.

- 12 Feb 20

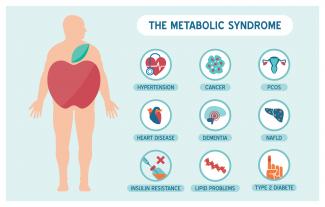

Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of risk factors that increase one’s chances of developing serious illnesses in the future. Metabolic syndrome doubles the chance of developing cardiovascular disease while increasing the risk of diabetes, fatty liver, and several types of cancers.[1][2]

- 09 Jan 20

Premenstrual symptoms affect up to 80% of women. For many, these symptoms are bothersome but do not necessarily impact their daily functioning. Premenstrual syndrome (PMS), however, affects up to 20% of women. This diagnosis is defined by a woman’s experience of at least one physical and one psychiatric symptom each month in the second half of her cycle (7–14 days before her period), that alleviate with or shortly after the onset of menses.

- 09 Mar 20

The human gastrointestinal tract (GIT) alone contains 1014 microorganisms including bacteria, viruses, and fungi. That’s approximately 100 times more microbial cells than human cells, which shows how much of an impact they can have on human health.

- 09 Jan 20

What is ketosis and the keto diet? Is it good for you, or is it just another lifestyle trend that we’ll forget about in a few years? In this article, we’ll try to answer this question and review the available evidence to see what we can learn.

- 05 May 20

Acne (or acne vulgaris) is one of the most common skin conditions, affecting 64% of people in their 20s and 43% of people in their 30s. It affects the pilosebaceous units of the skin, which is essentially the oil gland and hair follicle. It usually affects the largest, hormone-responsive sebaceous glands such as those on the face, chest, neck and back.

- 08 Jul 20

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is one of the most common endocrine disorders. PCOS affects one in every five women of the reproductive age.

- 13 Apr 15

The prevalence of overweight and obesity has skyrocketed in North America over recent years, and weight management strategies employed have had little widespread success. Both science and the public have been interested in natural and synthetic weight loss aids for decades, the most recent slimming agent being Garcinia cambogia (G. cambogia) and its extract (−)‑hydroxycitric acid (HCA).

The prevalence of overweight and obesity has skyrocketed in North America over recent years, and weight management strategies employed have had little widespread success. Both science and the public have been interested in natural and synthetic weight loss aids for decades, the most recent slimming agent being Garcinia cambogia (G. cambogia) and its extract (−)‑hydroxycitric acid (HCA). - 05 Jun 14

Today’s modern diet may lead to numerous chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. These health conditions are strongly linked to affluence. The Paleolithic Diet (or Paleo diet) has been extremely popular in communities that are health-conscious. It has steadily been gaining momentum and is now being featured on television, in magazines, and on various blogs. It is worthwhile being a bit cautious before making any major changes, since some of the marketing done around the Paleo diet can sometimes be extreme.17 Jul 1605 Jul 1922 Dec 15 According to Statistics Canada, results from the 2009 to 2011 Canadian Health Measures Survey (CHMS) indicate that 1 in 5 Canadian adults aged 18 to 79 had metabolic syndrome. Metabolic Syndrome, also known as Syndrome X, Insulin Resistance Syndrome, or Mets refers to a cluster of conditions that occur together. These conditions include high blood pressure, high blood sugar levels, excess body fat around the waist or mid-central obesity, and abnormal cholesterol levels. 13 Oct 1502 Sep 1502 Sep 15

According to Statistics Canada, results from the 2009 to 2011 Canadian Health Measures Survey (CHMS) indicate that 1 in 5 Canadian adults aged 18 to 79 had metabolic syndrome. Metabolic Syndrome, also known as Syndrome X, Insulin Resistance Syndrome, or Mets refers to a cluster of conditions that occur together. These conditions include high blood pressure, high blood sugar levels, excess body fat around the waist or mid-central obesity, and abnormal cholesterol levels. 13 Oct 1502 Sep 1502 Sep 15

Newsletter

Most Popular

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13