A common concern presenting in general practice is hair loss. Hair is an integral aspect of our identity and feelings of self-esteem, and it offers an element of aesthetic expression for many. To see it recede or thin can be a challenging experience. This article will first review notable information pertaining to the hair physiology, along with key aspects relating to male and female patterns of hair loss (androgenic alopecia). In addition to the established forms of drug therapies, various device-based treatments, and the range of approaches offered through naturopathic approaches, additional topical-based treatments have emerged in recent years. Many of these have an established set of preclinical research associated with them, alongside clinical trials, which we will explore.

Hair Physiology

Hair Physiology

To best appreciate how topical agents impact hair growth, it is essential to briefly review certain aspects of hair physiology. The typical human scalp has over 100,000 hairs. Unlike other animals, human hair growth and loss is not experienced in a synchronized uniform fashion, such as seasonally or cyclically, but is more random. As such, hair loss is a continuous experience, with up to 100 hairs normally being shed each day, and up to 200 when hair is shampooed. There exist three primary phases of the hair growth cycle:

- Anagen, representing the active-growing phase, encompasses 90–95% of all scalp hairs at any given time, and last 2–6 years.

- Telogen, the resting phase, accounts for 5–10% of scalp hairs, and lasts 2–3 months.

- Finally, catagen is the transition phase between anagen and telogen, and last 2–3 weeks.

Why can we grow hair from our scalp to be long, as compared to that of our eyelashes, legs, or forearms? The simple reason is that scalp hairs stay in the anagen phase for up to six years, as compared to roughly six months or less for those other locations. Within the lower hair bulb is the hair matrix, which contains the rapidly dividing cells destined to become the hair shaft. Within the matrix, it is the signalling between the cells of the dermal papilla and the surrounding follicular epithelium which drives the hair cycle. Mediators such as cytokines and growth hormones are at the heart of such communication, and as we will see, can themselves be influenced by topical agents which, in turn, influence the hair-growth cycle. ,

Androgenic Alopecia: A Brief Review

Androgenic alopecia (AGA) is a hereditary-based sensitivity of scalp hair follicles to circulating androgen hormones. This leads to the symmetric, diffuse, and patterned miniaturization of hairs over mostly the crown, vertex, and frontal areas. This process involves the regression of thick, pigmented terminal hairs back to the thinner, shorter, and less-pigmented vellus hairs. In AGA, the length of the anagen phase is gradually reduced over successive hair cycles, as is the ratio between anagen and telogen hairs.

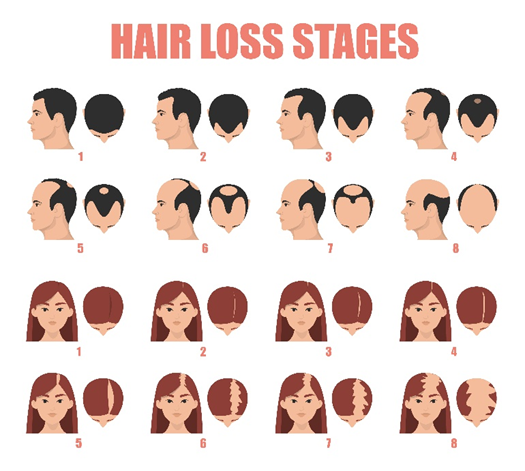

The two primary patterns of AGA include female and male patterns of hair loss. Although variations exist, the female pattern typically involves diffuse hair thinning over the midfrontal/central scalp, with retention of the frontal hairline and no experience of balding. By contrast, male-pattern alopecia is characterized by a gradual recession of the hairline alongside hair loss over the vertex. Balding over these areas is also experienced. , Androgen hormones are heavily implicated in male AGA; however, the picture is less clear for female AGA, as both androgen-dependent and androgen-independent mechanisms are postulated. In terms of the androgen influence, circulating testosterone is converted into dihydrotestosterone (DHT) via the 5α‑reductase enzyme, of which two distinct types (I and II) exist within various parts of the hair follicle. DHT has a higher binding affinity for the androgen receptor than does testosterone. Within the hair follicle, the androgen receptor is principally found in the dermal papilla cells — basically giving DHT access to the “control room,” you could say, with regards to the various factors which mediate the hair cycle. For example, DHT induces the dermal papillary cells to secrete transforming growth factor‑β (TGF‑β), which drives the hair cycle toward the induction of catagen while also preventing the re‑entry from telogen to anagen. In addition to the role of DHT, recent findings suggest a role for (micro) inflammatory processes, fibrosis, improper hair follicle anchoring within the extracellular matrix, and prostaglandin activity in the genesis of AGA. However, conflicting findings and debates surround these findings.

The two primary patterns of AGA include female and male patterns of hair loss. Although variations exist, the female pattern typically involves diffuse hair thinning over the midfrontal/central scalp, with retention of the frontal hairline and no experience of balding. By contrast, male-pattern alopecia is characterized by a gradual recession of the hairline alongside hair loss over the vertex. Balding over these areas is also experienced. , Androgen hormones are heavily implicated in male AGA; however, the picture is less clear for female AGA, as both androgen-dependent and androgen-independent mechanisms are postulated. In terms of the androgen influence, circulating testosterone is converted into dihydrotestosterone (DHT) via the 5α‑reductase enzyme, of which two distinct types (I and II) exist within various parts of the hair follicle. DHT has a higher binding affinity for the androgen receptor than does testosterone. Within the hair follicle, the androgen receptor is principally found in the dermal papilla cells — basically giving DHT access to the “control room,” you could say, with regards to the various factors which mediate the hair cycle. For example, DHT induces the dermal papillary cells to secrete transforming growth factor‑β (TGF‑β), which drives the hair cycle toward the induction of catagen while also preventing the re‑entry from telogen to anagen. In addition to the role of DHT, recent findings suggest a role for (micro) inflammatory processes, fibrosis, improper hair follicle anchoring within the extracellular matrix, and prostaglandin activity in the genesis of AGA. However, conflicting findings and debates surround these findings.

Conventional treatment strategies for male AGA include the use of minoxidil, a topical medication which works to increase the duration of anagen phase, stimulates follicles at rest to grow, and enlarges miniaturized follicles. Approximately one-third of users will achieve what’s called “cosmetically obvious” regrowth; in other words, long enough to resume combing and cutting in the affected area. Finasteride is an oral medication which inhibits the type II 5α‑reductase enzyme, helping address the impact of DHT on AGA hair loss. It can take close to six months or more before results are noticed with either of these treatments, and continued use is required to maintain the effects. For female AGA, minoxidil treatment has shown clinical benefits as well. In clinical situations where excess androgens are contributing toward hair loss, such as in polycystic ovarian syndrome, then antiandrogen medications may comprise part of the treatment approach. A Cochrane Database review suggested that, overall, evidence indicates finasteride therapy for female-pattern hair loss shows no major benefit over placebo. Finasteride is also contraindicated in women who are or may become pregnant, owing to detrimental effects on a male fetus. Other treatments for AGA include low-level laser-light therapy, microneedling, platelet-rich plasma therapy, various cosmetic products (including hair pieces, wigs, tinted hairsprays, and lotions), and various surgical approaches. , Naturopathic approaches can vary and are individualized to each patient. They may include the likes of dietary therapy; oral supplementation such as saw palmetto (Serenoa repens), owing to its inhibitory effect on DHT formation; , as well as traditional Chinese medicine–based treatments, including acupuncture. Management of health concerns contributing toward hair loss is another major benefit of naturopathic care.

Topical Agents for Male and Female Patterns of Hair Loss

Caffeine Preclinical Data (In Vitro and Ex Vivo)

Interest in exploring the role of topical caffeine is associated with its role in promoting cell proliferation, achieved through the support of cellular metabolism via the increase of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (AMP). Among the noted preclinical data supporting topical caffeine for AGA include stimulation of hair-follicle keratinocyte proliferation with noted hair-shaft elongation, , increased proliferation of both hair-matrix keratinocytes and outer-root sheath cells, , inhibition of 5α‑reductase, , and inhibition of apoptosis and necrosis.

Clinical Data

Clinical Data

A trial sought to contrast the effects of topical caffeine with those of minoxidil in a six-month randomized, open label, noninferiority trial of 161 male subjects with AGA (18–55 years of age). Subjects’ AGA was classified as Hamilton-Norwood grades III, III Vertex, IIIa, IV, IVa, or V, with 20%+ telogen ratio on trichogram, a microscopic assessment to determine a given hair’s phase within the hair cycle. Subjects applied, twice daily, either 0.2% caffeine solution (n = 82) or 5% minoxidil (n = 79) to the scalp. The study was manufacturer-sponsored. The primary endpoint was anagen rate determination, i.e., the change in proportion of anagen hairs from baseline. The authors stated how a noninferiority as a study seemed more appropriate given how the reference product of minoxidil is FDA approved. Therefore, the caffeine-based topical would be in direct comparison with a well-established treatment agent. Findings demonstrated how both treatments achieved the primary outcome, such that there was no significant between-group difference (p = 0.574). This kept within the 5% margin of noninferiority previously set for this trial. What’s more, significant improvements from baseline for both groups were achieved, with nonsignificant differences between them, including intensity of hair loss, hair strength, and progression of balding (all p < 0.01).

Topical Agent “Combos”: From Peptides to Herbal Medicines

Although the exploration of individual ingredients is common in preclinical studies, much of the commercial use of hair-loss cosmeceuticals combines them together within a formula. An example we will review involves various combinations of acetyl tetrapeptide‑3, biochanin A (derived from red clover [Trifolium pratense], and Panax ginseng.

Preclinical Data (In Vitro and Ex Vivo) Acetyl tetrapeptide‑3 is of interest in the realm of hair loss owing to the principal notion that it may offer a method by which to strengthen the extracellular matrix (ECM) structures, both surrounding and within the hair follicle, thus improving its “anchoring” into the local tissue. As a biomimetic peptide, it may stimulate the production of various ECM components, including various collagens.

Biochanin A, an isoflavone derived from red-clover extract (Trifolium pratense), has garnered interest for its potential to limit conversion of testosterone to DHT. In vitro data suggests how it may inhibit both types I and II isoenzyme forms of 5α‑reductase.

Panax ginseng, both in the form of whole-plant extracts and isolated ginsenosides, has enjoyed a plethora of preclinical research in relation to its effects on hair. Collectively, among the primary effects as determined through in vitro and animal trials include the inhibition of 5α‑reductase, apoptosis, and TGF‑β; as well as the activation of various mediators which drive anagen hair growth signalling, including expression of β‑catenin.

Clinical Data

Clinical Data

In addition to the preclinical data we reviewed, a team also reported on a four-month randomized, controlled trial (RCT) of 30 volunteers (gender not specified) with active “mild-to-moderate” hair loss (no AGA classification specified), all with less than 70% of hair strands in anagen phase. Twenty (20) drops of the test (n = 15) or placebo (n = 15) lotion was applied once daily to balding areas and massaged over whole scalp. The test lotion contained a 5% concentration of red-clover extract (titrated to contain 15 parts per million [ppm] biochanin A) and acetyl tetrapeptide‑3 (containing 300 ppm). Noted findings from this trial reaching significance include increased anagen hair density in test group after four months compared to baseline (p < 0.1]; increased anagen:telogen ratio by 46% over baseline in the test group (p ≤ 0.05); and a 33% reduction in the anagen:telogen ratio, compared to baseline, in the placebo group (p ≤ 0.05). Note: All authors were listed as members of the manufacturer’s research-and-development team.

A more recent study involved a six-month RCT of 16 men (AGA with Hamilton-Norwood stage III to IV‑vertex) and 16 women (AGA Ludwig type I to II), with a combined average age of 41.3 and average duration of AGA of 6.5 years. The participants were randomized into the herbal-extract group (n = 17) or a 3% minoxidil group (n = 15), with both groups applying their product twice daily over the scalp. The herbal extract product contained acetyl tetrapeptide‑3, biochanin A from red-clover extract (Trifolium pratense), and Panax ginseng (concentrations unspecified). Comparisons were made of each product to baseline and to each other. Noted findings reaching significance by six-months include clinical improvement as per an 8.3% increase of terminal hair count, versus baseline, for herbal extract (p = 0.009); and an 8.68% increase for the minoxidil group (p = 0.002). In this measure, there was no statistical difference found between the two groups (p = 0.306). Hair-mass index, a measure representing both hair density and diameter, was demonstrated to increase compared to baseline for both the herbal extract group (+13.8%; p = 0.008) and minoxidil group (+31.48%; p = 0.026), with, yet again, no significant differences found between the two groups (p = 0.158).

Rosemary Oil (Rosmarinus officinalis)

Another purported mechanism of stimulating hair regrowth is via the stimulation of (micro)circulation within the blood vessels surrounding the hair follicles. This is one reason as to why scalp self-massage is believed to itself provide some degree of benefit to hair, such as increased hair thickness. Certain hair cosmeceuticals, such as rosemary oil, are believed to also act via an enhancement of increased microcapillary perfusion.

Clinical Data

Clinical Data

A six-month randomized, single-blinded trial of 100 men with AGA (Hamilton-Norwood II—IV, majority were stage II) was performed. Either 1 ml of rosemary-oil lotion (containing 3.7 mg of 1.8 cineole per ml) or 2% minoxidil was applied twice daily by subjects. Noted findings reaching significance by six months included increased hair count measured at six-month mark in both groups v. baseline (rosemary oil: from 122.8 ± 48.9 at baseline to 129.6 ± 51.2, p < 0.05; for minoxidil: from 138.4 ± 38.0 at baseline to 140.7 ± 38.5, p < 0.05). No significant differences were found between the two groups by trial end (p > 0.05). On subject self-assessment, the percentage satisfaction with treatment (in terms of decreased hair loss) showed a slight significant difference favouring the rosemary group as compared to that of minoxidil by six months (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

As our understanding of the mechanisms underlying androgenic alopecia evolves, so too does the range of therapeutic options targeting such mechanisms. Research into natural compounds is quickly helping expand the spectrum of topical cosmeceutical agents which may efficiently address the hair-loss process of AGA from various vantage points. As more human trials are performed, this can help feed into an exciting period for developing more and more options for both women and men looking to manage hair loss and hair thinning.

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive brain disease that slowly eats away at memories and causes problems with thinking. As the degeneration progresses, it can lead to the inability to complete even simple tasks. Symptoms typically will begin to appear after the age of 60. Alzheimer’s is considered the most common cause of dementia, which means loss of cognitive functioning and the loss of some behavioural functioning.

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive brain disease that slowly eats away at memories and causes problems with thinking. As the degeneration progresses, it can lead to the inability to complete even simple tasks. Symptoms typically will begin to appear after the age of 60. Alzheimer’s is considered the most common cause of dementia, which means loss of cognitive functioning and the loss of some behavioural functioning.

As baby boomers head into their golden years, research and marketing have followed suit, offering skin-care and food products, as well as more invasive procedures that aim at providing youthful, flawless, glowing skin. As the focus shifts towards maintaining youth both in appearance and on the inside, people are turning to all sorts of treatments in an attempt to look and feel their best.

As baby boomers head into their golden years, research and marketing have followed suit, offering skin-care and food products, as well as more invasive procedures that aim at providing youthful, flawless, glowing skin. As the focus shifts towards maintaining youth both in appearance and on the inside, people are turning to all sorts of treatments in an attempt to look and feel their best.